Belleau Wood, 6 – 26 June 1918.

These Marines, caught on camera before the fight, were about to earn a name the world hadn’t heard yet. In the hell of Belleau Wood, the Germans would call them Teufelhunden (Devil Dogs)

Early in June of 1918, the 2nd U.S. Division was rushed into the line to plug a gap that the Germans had cut in the French lines. The Marine Brigade’s assignment was to “Hold the line at all hazards.” The German attack was eventually stopped and both sides consolidated their positions. The Germans facing the Marines were dug into defensive positions in a place called Bois de Belleau, or Belleau Wood. As Marines moved to the front, retreating French soldiers encouraged them to “fall back… retreat…” telling them that advancement was impossible. In classic Marine fashion Capt Lloyd Williams reportedly answered, “Retreat hell, we just got here!”

Poor battlefield intelligence and a lack of patrolling led the Marines to believe that the Germans did not occupy Belleau Wood. The Marines took up positions along the Paris-Metz road, the Germans’ fortified positions in Belleau Wood, and attacked on 6 June. They ran headlong into a regiment of German infantry with an interlocking network of machinegun nests and artillery support. For twenty days, the Marines fought the Germans before securing the woods. It was some of the fiercest fighting in Corps’ history and involved a great deal of hand-to-hand combat. It was not until 0700 on 26 June 1918 that a Marine rifle company reached the north edge of the woods.

Gunnery Sergeant Dan Daly led one of the charges across the wheat fields. To inspire his Marines, he was heard to say, “Come on, you sons of bitches! Do you want to live forever?” By evening, the Marines destroyed the German defensive line and pushed the Germans out of Bouresches. For five days the Marines pushed forward until 12 June when the last German defensive line was broken. The woods, except for a small corner, were controlled by the Marines. On 13 June, the Germans counterattacked, only to be repelled as Marine sharpshooters dropped the German attackers at 400 yards. In massive assaults, the Germans kept coming behind a wall of mustard gas. The Germans met death and failure against the Marines.

During the battle a Marine took a diary from a dead German soldier and while reading it, chanced upon some of the soldier’s last written words that stated his unit had found a nickname suitable for the gallant Marines–they called them “Teufelhunden” which means “Devil dogs”. The German high command classified the Marines as “Shock Troops,” a classification reserved only for the finest military organizations.

Casualties were extremely high. In less than three weeks of fighting, the Marine Brigade had taken over 50 percent casualties; 126 officers and 5,057 enlisted men were killed or wounded.

The French were extremely impressed with the U.S. Marines and their tenacious spirit. The French Parliament declared the Fourth of July to be a national holiday in honor of the Americans fighting in France. The French gave the Marines a citation for gallantry at Belleau Wood, the Croix de Guerre, and ordered that the Bois de Belleau be renamed the “Bois de la Brigade de Marine.”

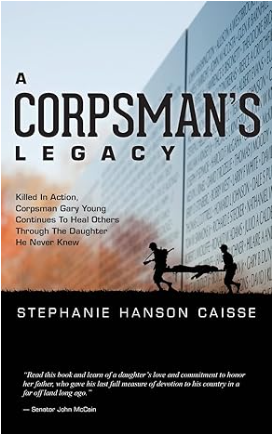

Our legacy lives through the stories we tell. The Suck Life wants yours! Make Chesty proud!

Our legacy lives through the stories we tell. The Suck Life wants yours! Make Chesty proud!

Semper Fidelis

Semper Fidelis

“But Belleau Wood had yet to be taken. It was an acid test of the Marines’ grit and dash. The French name means ” Wood of the Beautiful Waters,” but the marines, from the wealth of a cruel experience, called it Hellwood, with the accent on the first syllable. Later the French renamed it ” The Wood of the Marines,” in honor of those who shed their blood in driving the Boches out. That task was accomplished by a battalion of 958 men and 26 officers. At least that was the number of men who went in. Seven officers and 340 men remained when the rattle of the machine guns died away. Hours of bombardment by 50 batteries had destroyed all semblance of a wood, but in the tangled meshes of the debris the Germans still held their machine guns and worked them murderously. They were driven out by hand-to-hand fighting, in which the officers joined. Commands were impossible. It was every man for himself. It was one thing to take the wood: another to hold it. At night German airplanes flew over the battlefield, dropping bombs on the men below. By day their artillery searched the wood with shells, and their machine guns sprayed it with bullets. But the marines stayed there five days. It was necessary sometimes to send out for provisions or more munitions. No easy detail that. Once 45 men started out on such an errand. Three returned. Machine guns, gas and shells did for the rest. Of a party of 30 sent for ammunition six came back. There grew up the precarious profession of runners. Individuals, instead of parties, were sent for needed supplies and all were volunteers. ” Never once,” said the commanding officer in a later report, ” was there the slightest hesitation shown about carrying out these hazardous messages, and it was a miracle how they got through.”

Willis John Abbot. Soldiers of the sea: the story of the United States Marine Corps. Old Classics. Kindle Edition.