American Legion Editorial

By Jim Webb, September 2003

Against a backdrop of political mismanagement and social angst, history has failed to respect those who gave their all to the war in Vietnam.

Forty years ago, Asia was at a vital crossroads, moving into an uncertain future dominated by three different historical trends. The first involved the aftermath of the carnage and destruction of World War II, which left scars on every country in the region and dramatically changed Japan’s role in East Asian affairs. The second was the sudden, regionwide end of European colonialism, which created governmental vacuums in every second-tier country except Thailand and, to a lesser extent, the Philippines. The third was the emergence of communism as a powerful tool of expansionism by military force, its doctrine and strategies emanating principally from the birthplace of the Communist International: the Soviet Union.

Europe’s withdrawal from the region dramatically played into the hands of communist revolutionary movements, especially in the wake of the communist takeover of China in 1949. Unlike in Europe, these countries had never known Western-style democracy. In 1950, the partitioned country of Korea exploded into war when the communist North invaded South Korea, with the Chinese Army joining the effort six months later. Communist insurgencies erupted throughout Indochina. In Malaysia, the British led a 10-year anti-guerrilla campaign against China-backed revolutionaries. A similar insurgency in Indonesia brought about a communist coup attempt, also sponsored by the Chinese, which was put down in 1965.

The situation inside Vietnam was the most complicated. First, for a variety of reasons the French had not withdrawn from their long-term colony after World War II, making it easy for insurgents to rally the nationalistic Vietnamese to their side. Second, the charismatic, Soviet-trained communist leader Ho Chi Minh had quickly consolidated his anti-French power base just after the war by assassinating the leadership of competing political groups that were both anti-French and anti-communist. Third, once the Korean War armistice was signed in 1953, the Chinese had shifted large amounts of sophisticated weaponry to Ho Chi Minh’s army. The Viet Minh’s sudden acquisition of larger-caliber weapons and field artillery such as the 105-millimeter Howitzer abruptly changed the nature of the war and contributed heavily to the French humiliation at Dien Bien Phu.

Fourth, further war became inevitable when U.S.-led backers of the incipient South Vietnamese democracy called off a 1956 election agreed upon after Vietnam was divided in 1954. In geopolitical terms, this failure to go forward with elections was prudent, since it was clear a totalitarian state had emerged in the north. President Eisenhower’s frequently quoted admonition that Ho Chi Minh would get 75 percent of the vote was not predicated on the communist leader’s popularity but on the impossibility of getting a fair vote in communist-controlled North Vietnam. But in propaganda terms, it solidified Ho Chi Minh’s standing and in many eyes justified the renewed warfare he would begin in the south two years later.

In 1958, the communists unleashed a terrorist campaign in the south. Within two years, their northern-trained squads were assassinating an average of 11 government officials a day. President Kennedy referred to this campaign in 1961 when he decided to increase the number of American soldiers operating inside South Vietnam. “We have talked about and read stories of 7,000 to 15,000 guerrillas operating in Vietnam, killing 2,000 civil officers a year and 2,000 police officers a year – 4,000 total,” Kennedy said. “How we fight that kind of problem, which is going to be with us all through this decade, seems to me to be one of the great problems now before the United States.”

Among the local populace, the communist assassination squads were the “stick,” threatening to kill anyone who officially affiliated with the South Vietnamese government. Along with the assassination squads came the “carrot,” a highly trained political cadre that also infiltrated South Vietnam from the north. The cadre helped the people prepare defenses in their villages, took rice from farmers as taxes and recruited Viet Cong soldiers from the local young population. Spreading out into key areas – such as those provinces just below the demilitarized zone, those bordering Laos and Cambodia, and those with future access routes to key cities – the communists gained strong footholds.

The communists began spreading out from their enclaves, fighting on three levels simultaneously. First, they continued their terror campaign, assassinating local leaders, police officers, teachers and others who declared support for the South Vietnamese government. Second, they waged an effective small-unit guerrilla war that was designed to disrupt commerce, destroy morale and clasp local communities to their cause. And finally, beginning in late 1964, they introduced conventional forces from the north, capable of facing, if not defeating, main force infantry units – including the Americans – on the battlefield. Their gamble was that once the United States began fighting on a larger scale – as it did in March 1965 – its people would not support a long war of attrition. As Ho Chi Minh famously put it, “For every one of yours we kill, you will kill 10 of ours. But in the end it is you who will grow tired.”

Ho Chi Minh was right. The infamous “body counts” were continuously disparaged by the media and the antiwar movement. Hanoi removed the doubt in 1995, when on the 20th anniversary of the fall of Saigon officials admitted having lost 1.1 million combat soldiers dead, with another 300,000 “still missing.”

Communist losses of 1.4 million dead compared to America’s losses of 58,000 and South Vietnam’s 245,000 stand as stark evidence that eliminates many myths about the war. The communists, and particularly the North Vietnamese, were excellent and determined soldiers. But the “wily, elusive guerrillas” that the media loved to portray were not exclusively wily, elusive or even guerrillas when one considers that their combat deaths were four times those of their enemies, combined. And an American military that located itself halfway around the world to take on a determined enemy on the terrain of the enemy’s choosing was hardly the incompetent, demoralized and confused force that so many antiwar professors, journalists and filmmakers love to portray.

Why Did We Fight?

The United States recognized South Vietnam as a political entity separate from North Vietnam, just as it recognized West Germany as separate from communist-controlled East Germany and just as it continues to recognize South Korea from communist-controlled North Korea. As signatories of the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization, we pledged to defend South Vietnam from external aggression. South Vietnam was invaded by the north, just as certainly, although with more sophistication, as South Korea was invaded by North Korea. The extent to which the North Vietnamese, as well as antiwar Americans, went to deny this reality by pretending the war was fought only by Viet Cong soldiers from the south is, historically, one of the clearest examples of their disingenuous conduct. At one point during the war, 15 of North Vietnam’s 16 combat divisions were in the south.

How Did We Fight?

The Vietnam War varied year by year and region by region, our military’s posture unavoidably mirroring political events in the United States. Too often in today’s America we are left with the images burned into a weary nation’s consciousness at the very end of the war, when massive social problems had been visited on an army that was demoralized, sitting in defensive cantonments and simply waiting to be withdrawn. While reflecting America’s final months in Vietnam, they hardly tell the story of the years of effort and battlefield success that preceded them.

Little recognition has been given in this country of how brutal the war was for those who fought it on the ground and how well our military performed. Dropped onto the enemy’s terrain 12,000 miles away from home, America’s citizen-soldiers performed with a tenacity and quality that may never be truly understood. Those who believe the war was fought incompetently on a tactical level should consider the enormous casualties to which the communists now admit. And those who believe that it was a “dirty little war” where the bombs did all the work might contemplate that it was the most costly war the U.S. Marine Corps has ever fought. Five times as many Marines died in Vietnam as in World War I, three times as many as in Korea. And the Marines suffered more total casualties, killed and wounded, in Vietnam than in all of World War II.

Another allegation was that our soldiers were over-decorated during the Vietnam War. James Fallows says in his book “National Defense” that by 1971, we had given out almost 1.3 million medals for bravery in Vietnam, as opposed to some 1.7 million for all of World War II. Others have repeated the figure, including the British historian Richard Holmes in his book “Acts of War.” This comparison is incorrect for a number of reasons. First, these totals included air medals, rarely awarded for bravery. We awarded more than 1 million air medals to Army soldiers during Vietnam. Air medals were almost always given on a points basis for missions flown, and it was not unusual to see a helicopter pilot with 40 air medals because of the nature of his job.

If we compare the top three actual gallantry awards, the Army awarded:

289 Medals of Honor in World War II and 155 in Vietnam

4,434 Distinguished Service Crosses in World War II and 846 in Vietnam

73,651 Silver Stars in World War II against 21,630 in Vietnam

The Marine Corps, which lost 103,000 killed or wounded out of some 400,000 sent to Vietnam, awarded:

47 Medals of Honor (34 posthumously)

362 Navy Crosses (139 posthumously)

2,592 Silver Stars

Second, although the Army awarded another 1.3 million “meritorious” Bronze Stars and Army Commendation Medals in Vietnam, this was hardly unique. After World War II, Army Regulation 600-45 authorized every soldier who had received either a Combat Infantryman’s Badge or a Combat Medical Badge to also be awarded a meritorious Bronze Star. The Army has no data regarding how many soldiers received Bronze Stars through this blanket procedure.

Atrocities?

We made errors, although nowhere on the scale alleged by those who have a stake in disparaging our effort. Fighting a well-trained enemy who seeks cover in highly contested populated areas where civilians often assist the other side is the most difficult form of warfare. The most important distinction is that the deliberate killing of innocent civilians was a crime in the U.S. military. We held ourselves accountable for My Lai. And yet we are still waiting for the communists to take responsibility for the thousands of civilians deliberately killed by their political cadre as a matter of policy. A good place for them to start holding their own forces accountable would be Hue, where during the 1968 Tet Offensive more than 2,000 locals were systematically executed during the brief communist takeover of the city.

What Went Wrong?

Beyond the battlefield, just about everything one might imagine.

The war was begun, and fought, without clear political goals. Its battlefield complexities were never fully understood by those who were judging, and commenting upon, American performance. As a rifle platoon and company commander in the infamous An Hoa Basin west of Da Nang, on any given day my Marines could be fighting three different wars: one against terrorism, one against guerrillas and one against conventional forces. The implications of these challenges, as well as our successes in dealing with them, never seemed to penetrate an American populace inundated by negative press stories filed by reporters, particularly television journalists, who had no clue about the real tempo of the war. And one of the most under-reported revelations after the war ended was that several top reporters were compromised while in Vietnam, by communist agents who had managed to gain employment as their assistants, thus shaping in a large way their reporting.

Most importantly, Vietnam became an undeclared war fought against the background of a highly organized dissent movement at home. Few Americans who grew up after the war know that a large part of this dissent movement was already in place before the Vietnam War began. Many who wished for revolutionary changes in America had pushed for them through the vehicles of groups such as the ban-the-bomb movement in the 1950s and the civil-rights movement of the early and mid-1960s. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the infamous antiwar group Students for a Democratic Society was created at the University of Michigan through the Port Huron Statement in 1962 – three full years before American ground troops landed at Da Nang. The SDS hoped to bring revolution to America through the issue of race. They and other extremist groups soon found more fertile soil on the issue of the war.

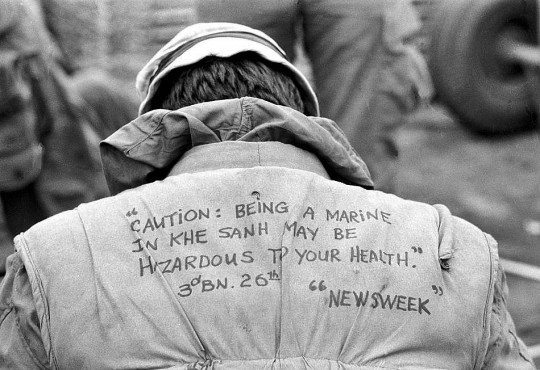

Former communist colonel Bui Tin, a highly placed propaganda officer during the war, recently published a memoir in which he specifically admitted a truth that was assumed by American fighting men for years. The Hanoi government assumed from the beginning that the United States would never prevail in Vietnam so long as the dissent movement, which they called “the Rear Front,” was successful at home. Many top leaders of this movement coordinated efforts directly with Vietnamese communist officials in Hanoi. Such coordination often included visiting the North Vietnamese capital – for instance, during the planning stages for the October 1967 march on the Pentagon – a few weeks before the siege of Khe Sanh kicked into high gear and a few months before the Tet Offensive.

The majority of the American people never truly bought the antiwar movement’s logic. While it is correct to say many wearied of an ineffective national strategy as the war dragged on, they never stopped supporting the actual goals for which the United States and South Vietnam fought. As late as September 1972, a Harris survey indicated overwhelming support for continued bombing of North Vietnam – 55 percent to 32 percent – and for mining North Vietnamese harbors – 64 percent to 22 percent. By a margin of 74 percent to 11 percent, those polled also agreed that “it is important that South Vietnam not fall into the control of the communists.”

Was It Worth It?

On a human level, the war brought tragedy to hundreds of thousands of American homes through death, disabling wounds and psychological scars. Many other Vietnam veterans were stigmatized by their own peers as a classic Greek tragedy played out before the nation’s eyes. Those who did not go, particularly among the nation’s elites, were often threatened by the acts of those who did and as a consequence inverted the usual syllogism of service. If I did not go to a war because I believed it was immoral, what does it say about someone who did? If someone who fought is perceived as having been honorable, what does that say about someone who was asked to and could have but did not?

Vietnam veterans, most of whom entered the military just after leaving high school, had their educational and professional lives interrupted during their most formative years. In many parts of the country and in many professional arenas, their having served their country was a negative when it came to admission into universities or being hired for jobs. The fact that the overwhelming majority of those who served were able to persist and make successful lives for themselves and their families is strong testament to the quality of Americans who actually did step forward and serve.

On a national level, and in the eyes of history, the answer is easier. One can gain an appreciation for what we attempted to achieve in Vietnam by examining the aftermath of the communist victory in 1975. A gruesome holocaust took place in Cambodia, the likes of which had not been seen since World War II. Two million Vietnamese fled their country – mostly by boat. Thousands lost their lives in the process. This was the first such diaspora in Vietnam’s long and frequently tragic history. Inside Vietnam, a million of the south’s best young leaders were sent to re-education camps; more than 50,000 perished while imprisoned, and others remained captives for as long as 18 years. An apartheid system was put into place that punished those who had been loyal to the United States, as well as their families, in matters of education, employment and housing. The Soviet Union made Vietnam a client state until its own demise, pumping billions of dollars into the country and keeping extensive naval and air bases at Cam Ranh Bay. In fact, communist Vietnam did not truly start opening up to the outside world until the Soviet Union ceased to exist.

Would I Do It Again?

Others are welcome to disagree, but on this I have no doubt. Like almost every Marine I have ever met, my strongest regret is that perhaps I could have done more. But no other experience in my life has been more important than the challenge of leading Marines during those extraordinarily difficult times. Nor am I alone in this feeling. The most accurate poll of the attitudes of those who served in Vietnam – Harris, 1980 – showed that 91 percent were glad they’d served their country, and 74 percent enjoyed their time in the service. Additionally, 89 percent agreed that “our troops were asked to fight in a war which our political leaders in Washington would not let them win.”

On that final question, history will surely be kinder to those who fought than to those who directed – or opposed – the war.

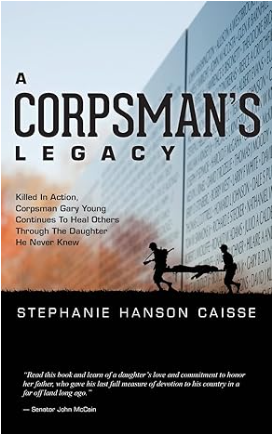

Our legacy lives through the stories we tell. The Suck Life wants yours! Make Chesty proud!

Our legacy lives through the stories we tell. The Suck Life wants yours! Make Chesty proud!

Semper Fidelis

Semper Fidelis